Climate change is nothing new. (Managing the survival of 7 or 8 billion humans is, but that’s another story). The ice sheets that covered northern North America during the past 2 million years have repeatedly advanced, then retreated during warming periods.

The ice is now mostly gone, but its effects on the land can be read clearly on many Raven maps, vividly on the Landforms titles, more subtly on our elevation tint and land cover versions. The Pacific Northwest exhibits particularly striking examples.

Glacially carved valleys are the most obvious legacy of recent ice, and are abundant in the mountains of the Northwest. Their distinctive U-shapes make them stand out in settings where it is now difficult to imagine glaciers at all.

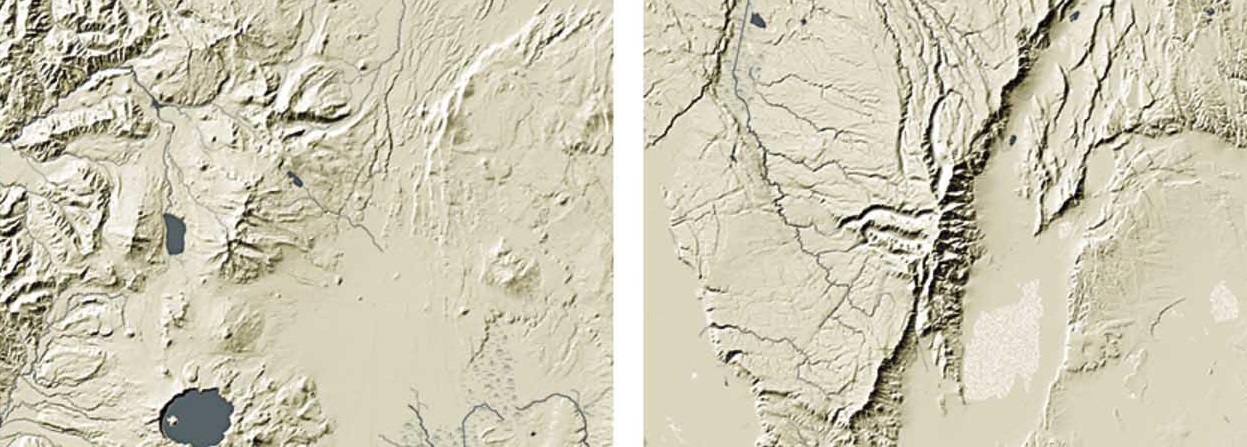

Oregon Landforms & Rivers map (above): Glacial valleys are prominent coming down off the high ridges north of Crater Lake (left), and even more striking on the Steens Mountains in eastern Oregon (right).

Glacial advances scrape off land surfaces on a vast scale and grind rock to powder. Retreats expose bare silt to the wind, which can spread it widely, as in the farmlands of the American corn belt, or pile in deep deposits like the rolling hills of the Palouse region of western Washington and eastern Idaho.

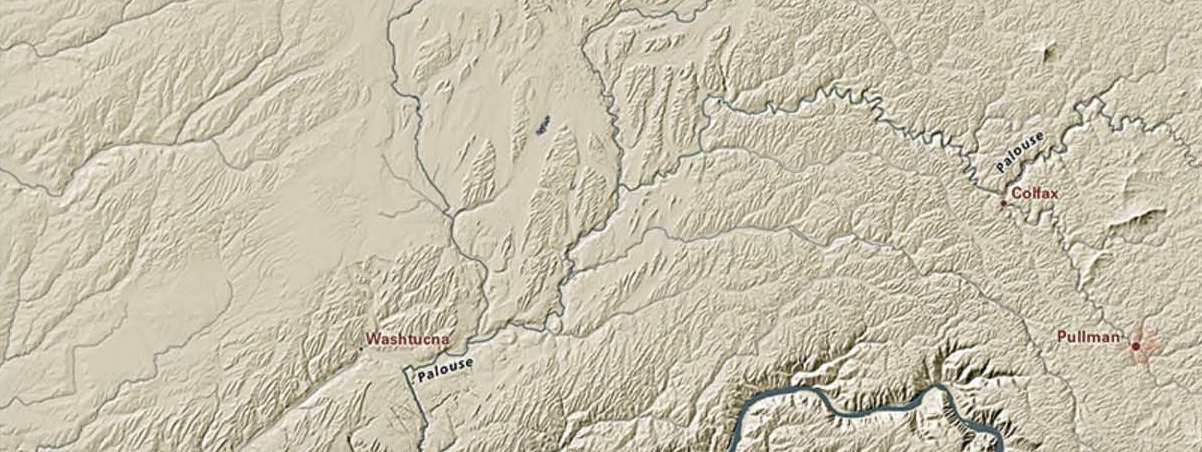

Washington Landform & Rivers (above): The wind-formed Palouse Hills extend in a remarkably even, ocean-like manner.

The most recent Missoula deposits were blown from lands exposed by the many Missoula Floods. These, in turn, were the result of a long sequence of advancing glacial ice damming the Clark Fork river in western Montana, forming repeated generations of Glacial Lake Missoula. These ice dams failed repeatedly during warming periods, most recently around 15,000 years ago. The resulting sudden catastrophic floods stripped channels down to bare rock, cutting the Channeled Scablands at the western edge of the Palouse.

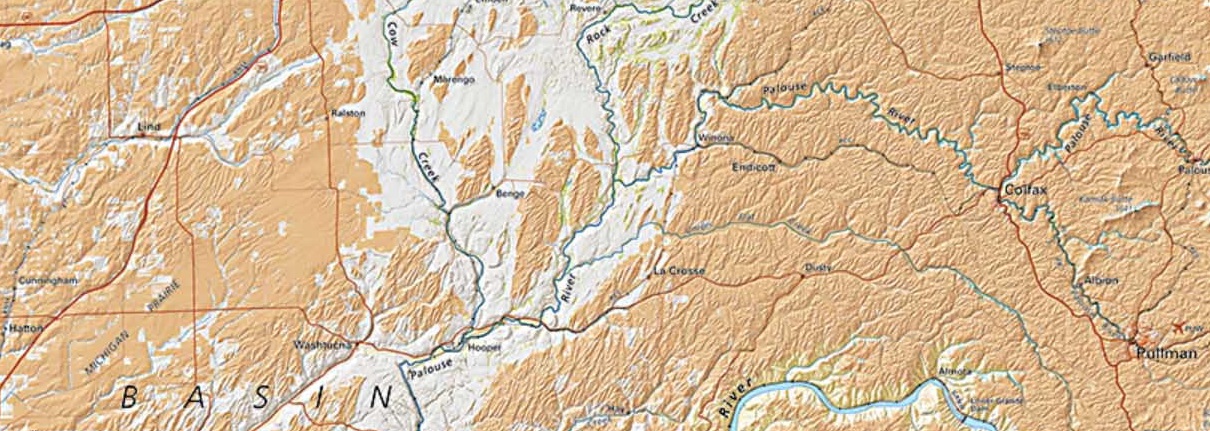

Washington Land Cover (above): Land Cover often illuminates land forms. Cultivated farmland, shown in pale orange, stands out against the barren Channeled Scablands.

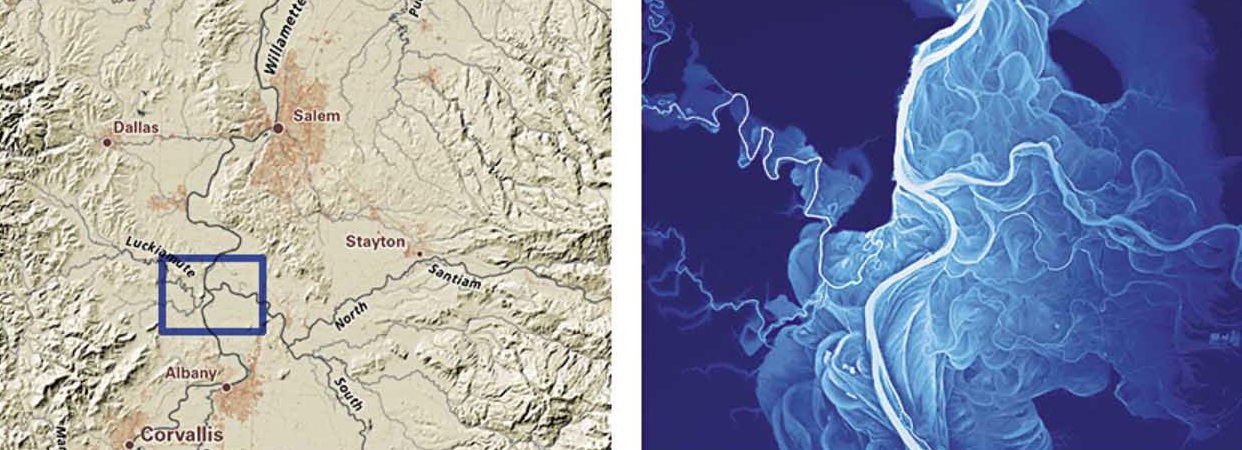

The Missoula Floods also scoured the Columbia River Gorge's nearly vertical walls, and filled Oregon's Willamette Valley with the silt that forms its present remarkable flat surface.

Oregon Landforms & Rivers (left) and Meanders (right) (above): The flat, even-grained Missoula Flood deposits give the Willamette Valley its remarkable flat surface in which an unusually complete record of river meanders is preserved.